OceanWatch Australia has, for 5 years, been working to provide an alternative tool for shoreline erosion. Turning old oyster shells into living shorelines.

This program has been a huge opportunity to develop a process through which old shells (essentially a waste product) can be treated, bagged and used to enhance the natural environment. It also provides universities with research opportunities and an excellent avenue to engage local communities in environmental work. Recreational fishermen, commercial fishermen, oyster farmers, Landcare groups, landholders, state government agencies, indigenous stakeholders, natural resource managers, local councils and hospitality heavyweights have all been engaged in the program. Shellfish reefs once formed the backbone of many temperate & subtropical estuaries, and whilst small populations continue to exist in most bays and estuaries, these are only a small fraction compared to the numbers seen pre-European settlement. In New South Wales, researchers estimate that over 99% of natural shellfish reefs have been lost due to pollution, sedimentation, disease and habitat loss or degradation from coastal development.

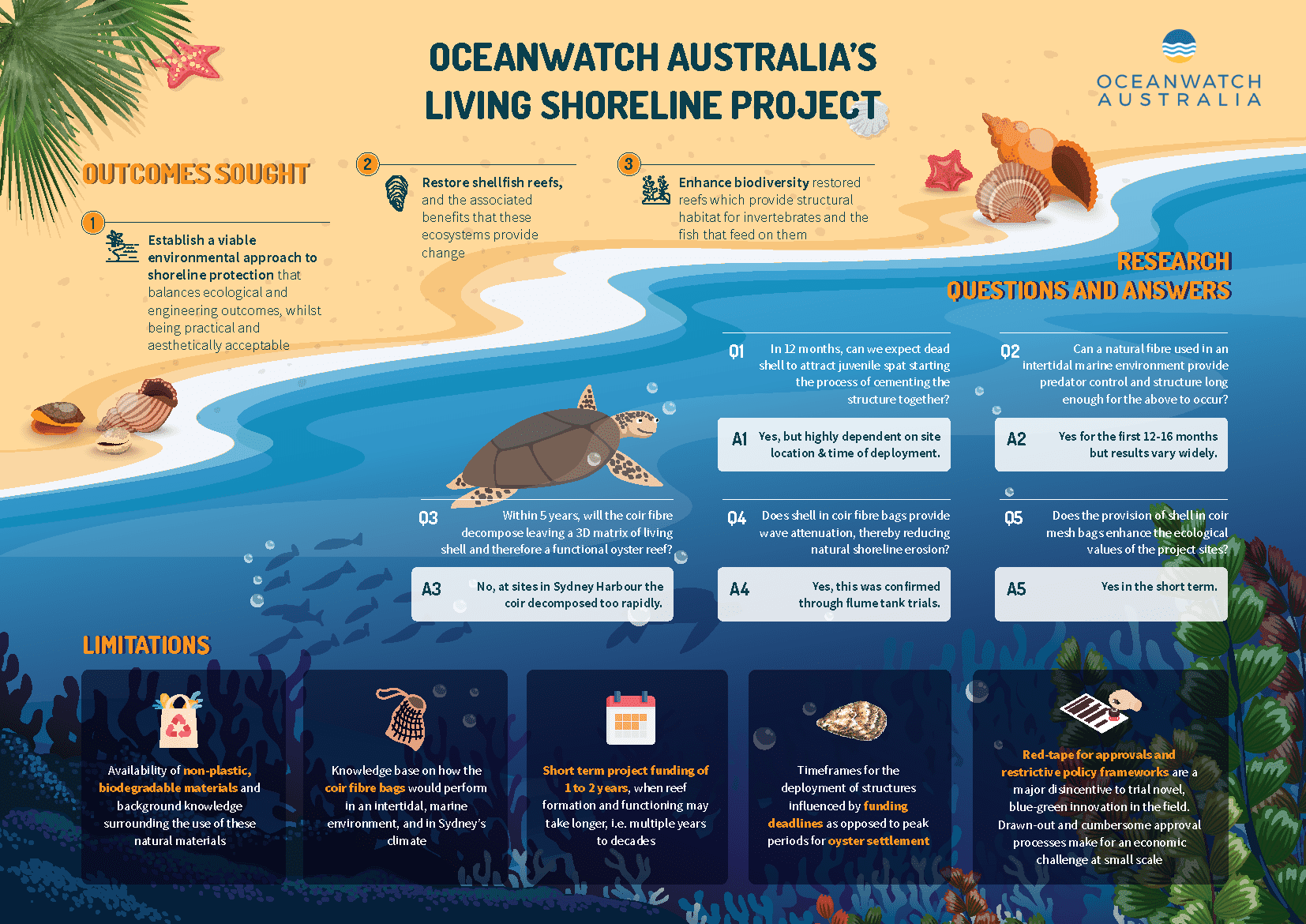

To restore these crucial habitats OceanWatch engages engineers and ecologists, to design “living shorelines”. The “living shoreline” concept started by taking old oyster shells and bagging them in coir (coconut fibre) mesh bags. These are then strategically pegged on eroded shorelines, providing a home for a multitude of other marine animals, and a surface on which free-swimming oyster larvae can settle.

Over time, the oysters can grow together to form a reef, and the coconut fibre breaks down. The project uses 100% natural, biodegradable materials ensuring that these living structures help to support, rather than degrade the surrounding ecosystem. The technique is extremely effective in the short to medium term providing habitat and wave energy absorption. However, its success is limited longer term as the current design of fibre breaks down too quickly and requires re-application every 12-18 months. Living Shorelines are therefore to be seen as a tool within a wider strategy.

Five sites in Sydney harbour, one in Brisbane waters and another on the Hastings River at Port Macquarie have all provided the opportunity to learn from and adapt our approach. Before commencing similar projects in your patch its worth investigating the underlying issues that caused the symptom you might be trying to address. Are conditions moving to favour the lifecycle of oysters which are dependent on healthy waters and correct salinity? Thriving oyster reefs can be a long-term (30 or more years) goal over which the site will experience booms and busts naturally.

Significant policy hurdles are still present which make this type of project difficult to implement in the intertidal if you lack the support of a government agency able and willing to take on the role of environmental approvals proponent. Start those conversations early as it could take 12 months or more for approvals to be processed. That said, refining techniques, understanding the benefits of using only natural materials, co-designing with existing ecology, and intervening for the long term in our intertidal foreshores remain a high priority for OceanWatch.

Funding support has been provided by the Australian Government, Sydney Coastal Councils Group, Greater Sydney Local Land Services, Landcare NSW and the NSW Recreational Fishing Trust.

To find out how you can get involved please email comms@oceanwatch.org.au

PROJECT REPORTS

Sydney Harbour Report

Brisbane Water Report

The Living Shorelines project contributes towards UN Sustainable Development Goals 6, 14, and 15 by taking action for the restoration of oyster reefs, utilising natural materials in innovative ways (shell and coconut fibres), increasing scientific knowledge and capacity through testing, monitoring and publishing and challenges planning approval processes to be inclusive of public good sub and intertidal biodiversity repair projects.